Making Thought Visible.

In this statement written at the end of my MA in Arts and Learning, I critically reflect on what I have learnt while making and researching how my art practice might fit now within an educational setting. I show how this new learning will feedback into my praxis for the future as an educator and artist.

Four years ago, I re-examined and updated my practice after raising my three daughters. I found Art School a much-changed place; it had become a place for creating critically conscious artists rather than a place to make art (Bishop, 2012). I became more critically aware of Arts’ potential to inform, elucidate, and educate. My role within that idea became a question for me. I began to engage with the notion that art could also be a vehicle to uplift. Following Jacques Rancière’s assertions, it starts turning the spectator into a conscious agent in transforming the world (Rancière,2009).

I employed Art to nurture and assist my children throughout their education. I used my limited resources and time as a mother, learning along the way. I now identify this process of research, making, and critical reflection, coupled with care, as a form of Paulo Freire’s conscientisation (Freire, 2021). This is also in line with bell hooks’ care and critical teaching in the classroom (hooks, 2010). I created a self-awareness of my social reality through action and reflection and was able to seek change when I needed it. This is the same methodology I was taught when young; it helped me develop an understanding of the world, allowing me to manage my life successfully. The MA in Arts and Learning has introduced me to the current educational doctrines that may be used to support these processes and pedagogies.

This year, I have confirmed the similarities between what I do when I teach and what I make within my kitchen studio. I have established that my artwork documents my response to my thoughts about what is physically in front of me or what is playing in my head. I realise that it is this process that keeps my practice alive, helping me to reflect and continue to uncover new ideas. This enables me to take on new views from those I work with and teach. This way of learning and teaching is in line with the praxis employed and advocated by bell hooks (2010), Paulo Freire (2021), Graham Sullivan (2010), and Tim Ingold (2022). It also fits with the methodologies of a/r/tography (Springgay, Irwin and Kind, 2005) and the Guattarian research-creation examined by Stephany Springgay (Springgay and Rotas, 2015).

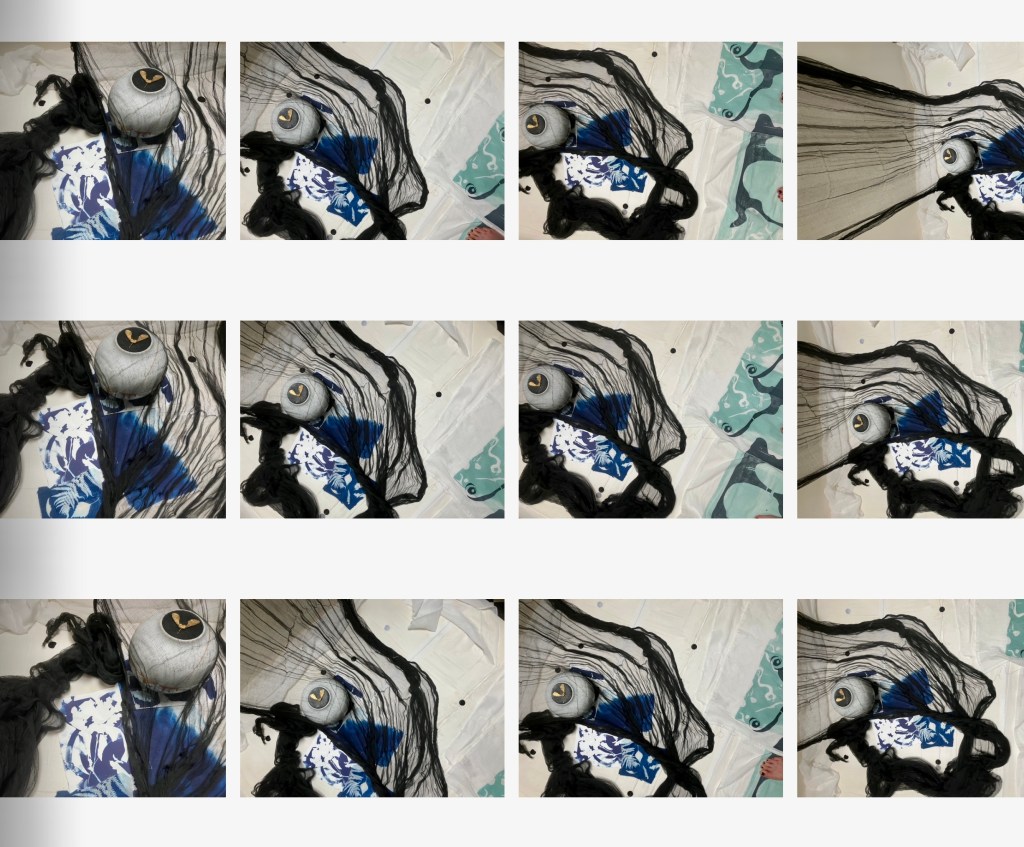

Employing these methods confirms Merleau-Ponty’s assertions concerning bodily perception and extension (Merleau-Ponty, 2004). I have arranged my thoughts, findings, and reflections and made them visible by creating vessels of knowledge. They take the physical form of zines, objects, or installations with links to my website. I have created expanded versions of what I like to call Memento Vivere. They are a snapshot of what I thought and found, reminding me that I am alive, proving I am here. Having completed the MA in Arts and Learning, my art pieces now include references to ideas that may open my practice more effectively to my students and audience.

This is a productive, cognitive and physical process where I bodily entangle myself in my idea and affirm my attraction for the everyday, engaging with phenomenology (Merleau-Ponty, 2002) and the beliefs of causal connections (Jung,1973). This structure enables me to balance my thoughts and find harmony within my existence. It may be considered an ecology or ecosophy (Guattari, 2018). I am in balance with my thoughts and my world. This is the praxis that I now take into the classroom, boiler room (art club) and my studio kitchen.

I have looked at ways of making these learning processes visible in the manner of Paul Klee (2013). I am revealing the praxis ideas of knowledge acquisition. I have allowed my curiosity to lead me. I have read, observed, skimmed books listened to lectures, watched films, and responded to the ideas surrounding our knowledge acquisition. In my response am using trees, jars, and bowls in my artwork. These vessels are talismans. They are artefacts which spark my thought process and give me anchors to allow me to track my ‘thought quest’. I have wondered how they have grown, what they mean, and who made them before jumbling them up to create metaphors to share my ideas. I ask where the lemon from my kitchen fits with the fish of knowledge from Irish lore and myself, the flying woman walking her dogs. My artwork evidences my thoughts, making my research visible. This is in line with Paul Klee’s assertion that art does not reproduce but makes things visible (Klee, 2013, p.118).

Art enriches both the educator and the educatee within the education system by enabling them to correspond (Ingold, 2016), play, and brew ideas together. Art creates and then re-creates to make the familiar strange: consequently, we see anew (Mannay, 2010). In this way, by plotting our everyday surroundings and creating a.r.t.ography (Springgay, Irwin and Kind, 2005), we connect and engage our senses (Wilson, 2002; Hooper, 1944). Art teaches and can elevate the mundane (Clark,1960; Morris,1887). By its nature, it encourages good working practice.

Having researched Ingold’s (2017) ideas surrounding the acquisition of knowledge and Merleau-Ponty’s (2004) thoughts about bodily extension and perception, and hooks’ thoughts on criticality and care (hooks, 2010), I now realise that the learning, playing, and the experiences we live outside school are as important as the formal knowledge we acquire in school; these are essential for creating whole, happy, and healthy individuals. When art exists inside and outside of school, it creates a conduit to connect our thinking to our physical selves and our environment. Art is a handy tool for education as it joins the dots and contains the data we have discovered. This knowledge may be dipped into and released at will. Art makes data alive.

In conclusion, I now clarify my thoughts and define my processes through writing. This ongoing correspondence confirms Ingold’s ideas of learning (2017). It has allowed me to communicate more effectively with my audience and exchange ideas with collaborators and students. I have created a praxis complete with current pedagogic theories. This allows me to examine subjects I have not been able to connect to before. In the future, I would like to investigate how my writing may become an active element within my final praxis.

Bishop, C. (2012) Artificial hells: participatory art and the politics of spectatorship. London, Brooklyn: Verso, Verso Books (ACLS Humanities E-Book). Available at: https://gold.idm.oclc.org/login?url=http://hdl.handle.net/2027/heb.32115 (Accessed: 14 February 2022).

Clark, S.K. (1960) Looking at Pictures. 1st Edition. John Murray Publishers Ltd.

Freire, P. (2021) Education for Critical Consciousness. Bloomsbury Academic.

Guattari, F. (2018) Ecosophy. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

hooks, bell (2010) Teaching critical thinking: practical wisdom. New York: Routledge.

‘hooks-2010-critical-thinking-chapter.pdf’ (no date). Available at: https://acurriculumjourney.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/hooks-2010-critical-thinking-chapter.pdf (Accessed: 30 April 2022).

Hooper, S.E. (1944) ‘Whitehead’s Philosophy: “Theory of Perception”’, Philosophy, 19(73), pp. 136–158. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3748241 (Accessed: 31 January 2022).

Ingold, T. (no date) Knowing from the Inside, Bloomsbury. Available at: https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/knowing-from-the-inside-9781350217157/ (Accessed: 11 May 2022).

Ingold, Tim (no date) Knowing From the Inside | The University of Aberdeen. Available at: https://www.abdn.ac.uk/research/kfi/ (Accessed: 12 May 2022).

Jung, C.G. (1973) Synchronicity: an acausal connecting principle. 1st Princeton/Bollingen paperback ed. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press (Princeton/Bollingen paperbacks, 297).

Klee, P. (2013) Paul Klee: Creative Confession and Other Writings. Harry N. Abrams.

Mannay, D. (2010) ‘Making the familiar strange: can visual research methods render the familiar setting more perceptible?’, Qualitative Research, 10(1), pp. 91–111. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794109348684.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (2002) Phenomenology of perception: an introduction. London: Routledge.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (2004) The World of Perception. 1st edition. Routledge.

Morris, W. (1887) The Aims of Art. Office of ‘The Commonweal,’.

Philipp, F.A. (1961) ‘Looking at Pictures, “Kenneth Clark” (Book Review)’, A.U.M.L.A.: Journal of the Australasian Universities Modern Language Association, 0(16), p. 258. Available at: https://www.proquest.com/docview/1311099628/citation/7C5D2280634E422EPQ/1 (Accessed: 24 February 2022).

Springgay, S., Irwin, R.L. and Kind, S.W. (2005) ‘A/r/tography as Living Inquiry Through Art and Text’, Qualitative inquiry, 11(6), pp. 897–912. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800405280696.

Springgay, S. and Rotas, N. (2015) ‘springgay. How do you make a classroom operate like a work of art? Deleuzeguattarian methodologies of research-creation’, International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 28(5), pp. 552–572. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2014.933913.

Sullivan, G. (2010) Art practice as research: inquiry in visual arts. 2nd ed.. Los Angeles ; London: SAGE.

Wilson, M. (2002) ‘Six views of embodied cognition’, Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 9(4), pp. 625–636. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03196322.